We need to talk about self-harm

TW: Discussions of self-harm and suicide

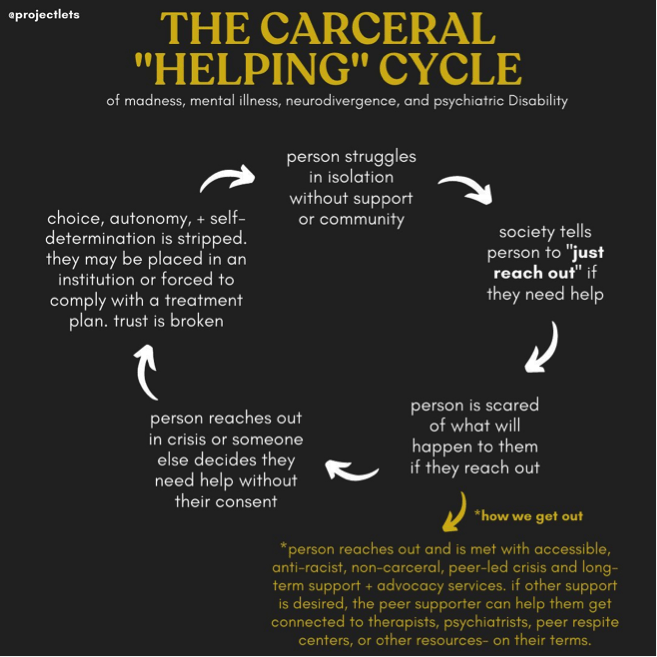

Systems in the US are built on the idea that those who are a “danger to themselves or others” can’t determine their own treatment. This deters those who are self harming or suicidal from seeking out care for fear of losing our autonomy.

In the university context, this trend has been seen in the use of involuntary withdrawal. Many universities have come under scrutiny for subjecting students with mental illness to involuntary withdrawal, with discrimination claims at the center of legal cases[i].

While I was in college, the mistreatment of students with mental illness, and their “being kicked off campus” was a prominent issue and impacted the student body’s ability to trust the university mental health system. During my first semester, I heard about a piece in our school newspaper titled “We just can’t have you here” in which a student described being forced to withdraw after self-harming and then seeking care[ii].

After this experience, struggling deeply with depression, I went into a tailspin. It seemed clear from this student’s account and the conversation on campus that our administrators were more concerned with protecting themselves from liability than engaging in thoughtful care for students. They also seemed to interpret all self-harm as imminent suicidal intent and were uninterested in whether a student’s mental health would be better off on campus or at home. In this moment I resolved to never go to a university affiliated health center or hospital if I needed help, and put the number of a community hospital in my phone, convinced that this would protect me from the administrative nightmare other students had experienced.

Luckily, I never had to use this number. My mental health improved throughout college, but I continued to see how the administration’s failures impacted the student body. Friends told me that they were afraid to go to the counselling center as they didn’t want the university to know anything about their mental health struggles. More and more students talked about people they knew who were “forced off campus”. And this all came to a head when the university paper published a suicide note of a student who discussed her fear of taking time off from the university as she might not be allowed back.

While many universities have made incremental changes to their policies, it is clear that we have to think harder about how we engage with people who self-harm, and in particular we must appreciate the importance of autonomy and personal decision-making when it comes to mental health care.

Universities are not the only setting in which those who are deemed a harm to themselves or others are at risk of having their autonomy stripped away. A range of standards using the “harm to self or others” determination are used to permit involuntary treatment of individuals with mental illness throughout the country. Like the university context, in which rules appear more focused on protecting the university than the student, I am convinced that these standards are not in fact in the best interest of those with mental illness.

I have been acutely aware of this in my own treatment. A few years ago, I was getting ready to leave for a research placement in Australia, and experiencing some suicidal ideation, as I had in the past and continue to have sometimes. I was honest about this with my psychiatrist at the time, who interpreted me to be in an acute self harm situation. I did my best to explain to him that I was not in fact self harming and had no suicidal intent. Still, he insisted that he would not let me leave the country if I did not add additional medications to my treatment. As I protested this, he said in a half joking tone, “at least I’m not talking about locking you up.”

In reality I know that I am privileged to have never experienced forced treatment, commitment or incarceration. I know that the courts could listen to a psychiatrist over a person with mental illness any day of the week, even if there are limits on the courts’ ability to mandate involuntary treatment. But this meant I stopped being honest with my providers and it took years to find providers I could trust enough to start opening up to these parts of myself again.

We have gotten to a point where lots of people can empathize with the experiences of depression and anxiety. But we need to talk more openly about what self-harm looks like and why people engage in it. To me, this means reckoning with those dark parts of humanity even if they scare us. When we start to recognize that self harming is in fact a legitimate expression of distress, and can present with or without mental illness, we can recognize a way forward that focuses on addressing the larger societal problems that underpin most suffering, which have become even more acute during the pandemic. To address self harm we must move past our siloed understanding of mental health and instead think about how we can create a world that we all want to live in; a world where less distress means we have less need to engage in self harm in the first place.

[i] https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2019/10/08/stanford-changes-leave-policies-mental-illness

[ii] https://yaledailynews.com/blog/2014/01/24/we-just-cant-have-you-here/

If you need support, we've compiled a list of resources

here.